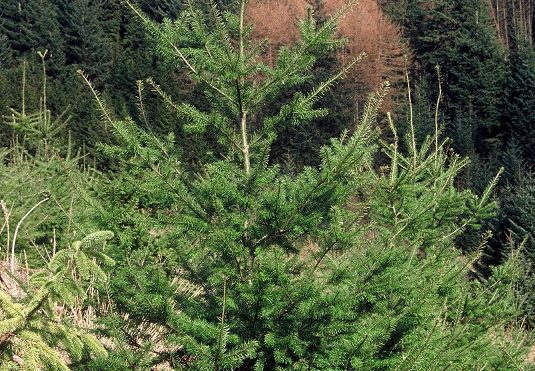

Douglas fir (DF)

Douglas-fir is one of the most economically important conifers in the Pacific northwest. Despite its common name Douglas-fir was discovered by Archibald Menzies in 1793 and introduced to Britain by David Douglas in 1872. Initially planted as estate specimens it is now mainly planted for commercial forestry. Some of the heritage specimens are now the tallest trees in Britain with examples reaching over 66 m in height.

A preference for deep fertile soils in sheltered sites has limited its use by many foresters. However, it is growing in popularity as an alternative forestry species to aid in diversification as the silvicultural knowledge has improved.

Douglas-fir is categorised as a principal tree species. These are species where our silvicultural knowledge provides confidence for their successful deployment across Britain. The species are either already widely used or are increasing in usage. They will continue to be important unless affected by a new pest or disease or become adversely affected by climate change.

Range

Native to the western parts of North America with a wide natural range stretching from British Columbia in the north to Mexico, and from the Pacific coast to Colorado in the east. Only the ‘green’ Douglas fir from the coastal part of this distribution is currently planted in Britain. Future research into wider provenances across and along its natural range may reveal possible adaptations to a warming climate.

Provenance Choice

Provenances from coastal Washington are recommended for western and more oceanic parts of Britain, while material from the south Washington Cascades can be used on suitable soils in drier zones of eastern Britain. In recent years, improved varieties from tested French seed orchards based on Washington and northern Oregon selections have also become available.

Site Requirements

This is a high yielding early successional species which produces a high-quality saw timber. It is best suited to humid regions with 700-2000 mm of rainfall, but it can also cope with summer droughts better than some other conifer species. It is cold hardy but suffers from exposure and therefore is suited to more sheltered areas such as lower to middle valley sides. It is damaged by late spring frosts and young trees can be prone to toppling on cold soils. It grows well on mineral soils of poor to medium fertility but requires adequate moisture and good soil aeration. It will not grow well on waterlogged or calcareous sites, or in competition with heather.

Further detail on the site requirements of Douglas-fir in current and future climates can be examined using the Forest Research Ecological Site Classification Decision Support System (ESC).

ECOLOGICAL SITE CLASSIFICATION TOOL

Silviculture

In Britain, planting density for Douglas fir has traditionally been around 2500 trees ha-1, but continental experience suggests lower densities (c. 1500 trees ha-1) can be used provided pruning is used to remove coarse branches. Both bareroot and containerised seedlings can be used, but seedlings must have a balanced root:shoot ratio for good establishment. The species is sensitive to cold storage and hot planting with careful handling is recommended. Douglas fir is palatable to deer so, protection against browsing is important.

Once established, growth is vigorous and on typical 50–60-year rotations productivity is often between 16 and 20 m3 ha-1 yr-1 or more. Regular selective thinning is required to favour the best quality stems. On sheltered sites longer rotations of 60-100 years can be used to produce large dimension high quality sawlogs. Such areas hold the tallest trees in Britain often exceeding 60 m in height.

Douglas fir has intermediate shade tolerance and can be grown in mixture with fast growing conifers such as larch, Japanese red-cedar, coast redwood or Sitka spruce, or with more shade tolerant species (e.g., true firs, beech) that will form an understorey in the mixed stand.

Under British conditions, coning does not begin until trees are around 40 years old, and good cone crops are infrequent. As a result, natural regeneration is less common than in other conifers, although it can be abundant in well thinned older stands especially on drier and warmer sites. It can be successfully managed using a continuous cover forestry approach, although it is probably best suited to irregular shelterwood or other systems that provide adequate light for regeneration to establish.

Because of its tolerance of dry summers, Douglas-fir could find an increased role in British forestry under climate change, particularly in forests in upland areas of eastern Britain provided the sites are not too exposed or prone to frosts. Potential alternatives could be pines on very dry sites, Sitka spruce on more exposed areas, or a range of broadleaves on sheltered fertile sites.

Pests and Pathogens

Douglas fir is usually considered moderately resistant to Heterobasidion (Fomes root and butt rot) as it suffers from little decay, but it is susceptible to root rot and therefore may become unstable as a result of attack by Heterobasidion. It is also affected by the fungal disease Swiss needle cast, Phaeocryptopus gaeumannii, which is widespread but relatively insignificant although climate change predictions (warmer, wetter springs) may increase the incidence.

Both mature and young trees can also be susceptible to infection by Phytophthora ramorum, although only when grown near other infected plants which are a major source of spores.

A new disease Phytophthora pluvialis identified in Cornwall in 2021 and subsequently further afield on western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla) and Douglas-fir. Suspected sightings of the of this disease anywhere in Great Britain should be reported using TreeAlert.

See our other tools and resources

Further Resources

Internal

In addition to the general sources of information for species the following are useful for Douglas-fir.

Fletcher, AM, and Samuel, CJA (2010) Choice of Douglas Fir Seed Sources for Use in British Forests. Forestry Commission Bulletin 129, Forestry Commission, Edinburgh.

External

In addition to the general sources of information for species the following are useful for Douglas-fir.

Reynolds, C., Kerr, G. and Forster, J. (2022) Alternatives to Corsican pine: evidence and experience from a long-term experiment in Thetford Forest. Quarterly Journal of Forestry 116: 26-33.

Spiecker, H., Lindner, M., and Schuler, J. (eds). Douglas-fir – an option for Europe. EFI What Science Can Tell Us 9, European Forest Institute, Joensuu, Finland, 126p.

Wilson, Scott McG. (2011) Using alternative conifers for productive forestry in Scotland. Forestry Commission Scotland, Edinburgh.