Understanding the biology of oak processionary moth (OPM) can help you to manage it.

The caterpillars are the larval stage of the insect’s life cycle. OPM gets part of its common and scientific names from the caterpillars’ distinctive habit of moving around in nose-to-tail processions on trees, and sometimes on the ground beneath host trees. They also frequently cluster together.

Both of Britain’s native species of oak, pedunculate and sessile oak, and several other oak (Quercus) species grown here, are susceptible to OPM. In a broadly descending order of susceptibility, they are:

Turkey oak (Quercus cerris), English or pendunculate oak (Q. robur), chestnut-leaved oak (Q. castaneifolia), white oak (Q. alba), Turner’s oak (Q. x turneri), Holm oak (Q. ilex), Algerian oak (Q. canariensis), Hungarian or Italian oak (Q. frainetto), sessile oak (Q. petraea) and cork oak (Q. suber).

The caterpillars feed on oak leaves. The damage which their feeding does to oak trees is quite distinctive and noticeable, because they tend to leave the leaves skeletonised, with the main veins remaining.

OPM caterpillars will feed on other species of broadleaved tree, but usually only if they are running short of oak leaves to feed on. They have been observed feeding on European sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa), hazel (Corylus avellana), beech (Fagus species), birch (Betula spp.) and hornbeam (Carpinus betulus), but they cannot usually complete their life-cycle on non-oak species.

Caterpillars can remain hidden in the soil around the base of the tree, so any trees seen with feeding damage, but no signs of larvae, should still be treated with suspicion and checked carefully. If the tree is in a pot or container, these should also be thoroughly checked.

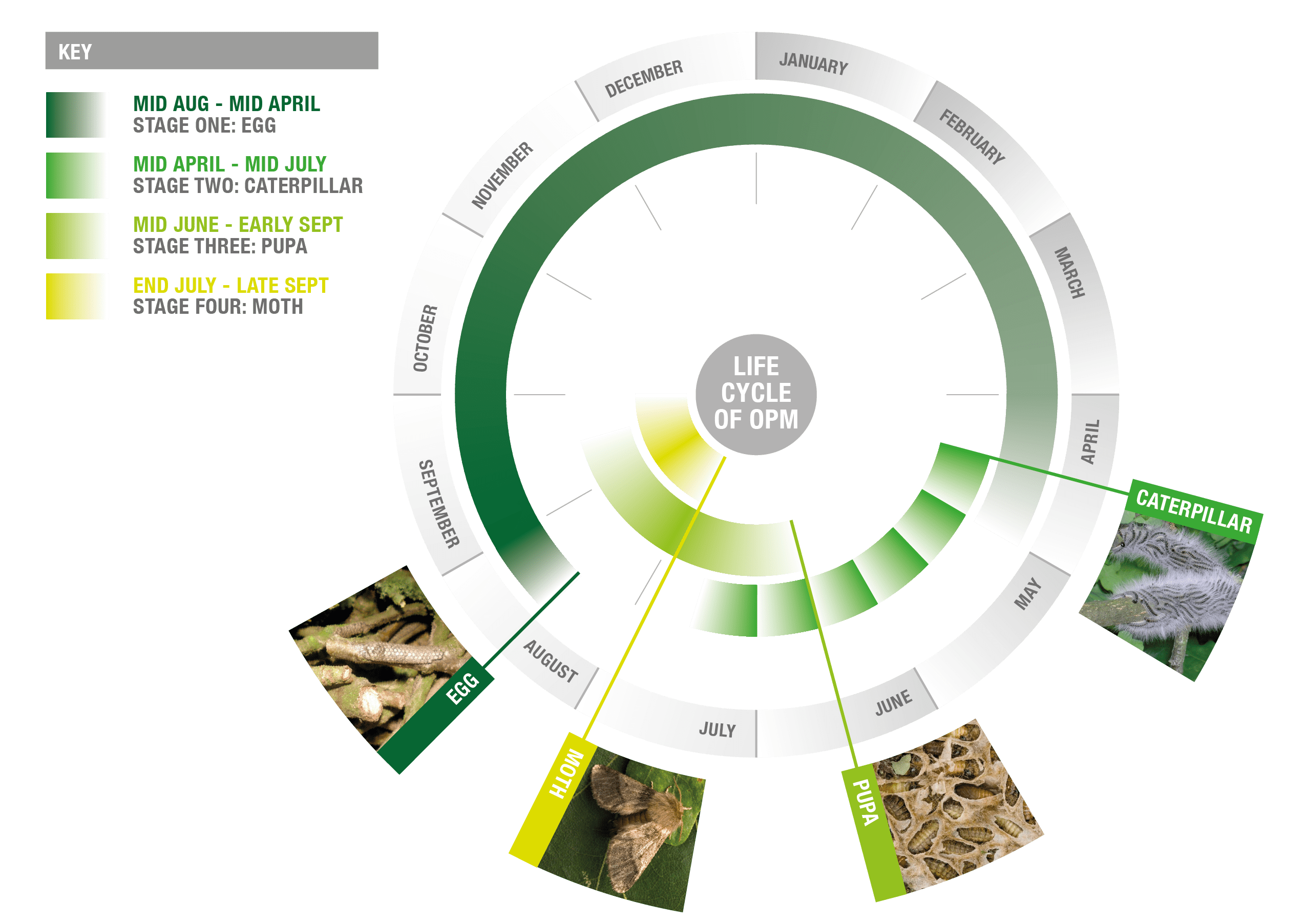

There is only one generation of OPM each year. The moths, the adult form of the species, usually emerge from pupation, mate and lay their eggs between late July and sometimes as late as the end of September. The eggs are laid in masses, or plaques, about 2-3 cm long on high branches and twigs. The egg plaques remain on the trees during the following autumn and winter.

Caterpillars emerge from the eggs between about mid-April and mid-May the following year, although emergence can start as early as March in warm weather. The caterpillars can go into a torpor – a coma-like state – for several days if the weather turns very cold again and leaf burst (the emergence of new leaves after winter) is interrupted, resulting in there being insufficient leaf material to feed on.

The caterpillar stage lasts for several weeks. After emerging from the eggs, they pass through six growth or developmental stages, known as ‘instars’, until the pupation stage. These instars are numbered L1 to L6, and they develop the urticating, or irritating, hairs from about L3.

The caterpillars descend lower down the trees as they get older and bigger, and build nests on the branches and trunks anywhere between ground level and high in the tree. They do not build nests among the leaves.

The nests are made of white silken webbing, and are often accompanied by white silken trails along the branches and trunks. These quickly become discoloured, and harder to see as a result. Sometimes nests can become dislodged from the trees and fall to the ground.

Older (L4-L6) caterpillars feed mainly at night and rest in their nests during the day.

From about late June to early August, the caterpillars retreat into the nests and moult to the pupal stage. The pupae remain in the nests during this period until they are ready to emerge as adult moths.

The final, adult stage in the life cycle is the moth. The first moths emerge from their pupae, shedding their pupal cases as they do so, about the middle of July, and the last ones can emerge late in September. Both sexes live for only three to four days as adults. Males are strong flyers, capable of flying up to 20 km (12 miles).

Females do not appear to disperse as far as males. Most tend to stay within the vicinity of the nest they emerged from. However, some females can disperse over reasonable distances, and this can explain the occurrence of OPM in locations where it has not been observed before.

The moths are difficult to distinguish from some other species of moth, so we do not require reports of them. However, we do accept reports of moths, especially females, caught in light traps by moth recorders who know how to accurately identify them. Reports can be made to opm@forestrycommission.gov.uk.

Knowing the approximate timings of the different life stages will help you understand what to look for, and what action is best, and this is set out in more detail in the next section.