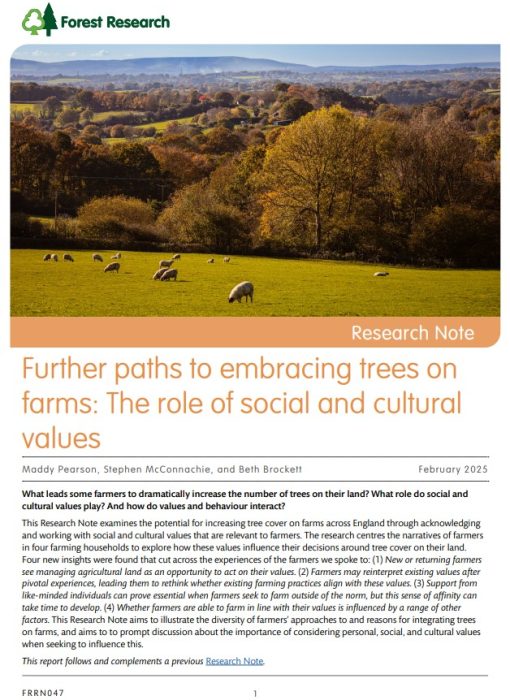

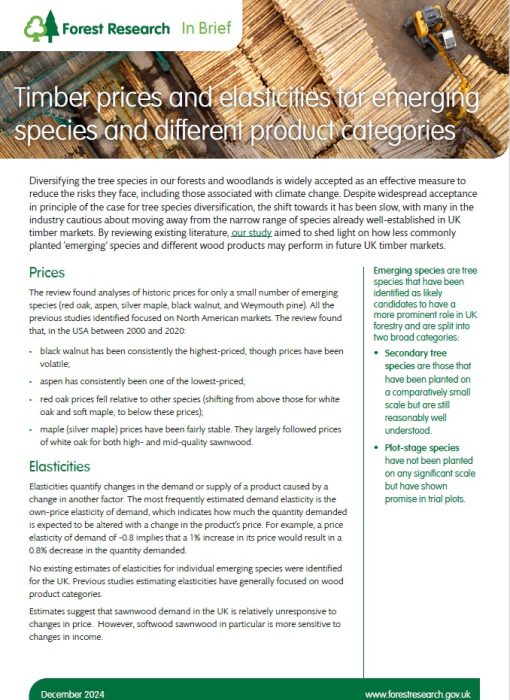

The management and creation of woodland for biodiversity and wider environmental benefits

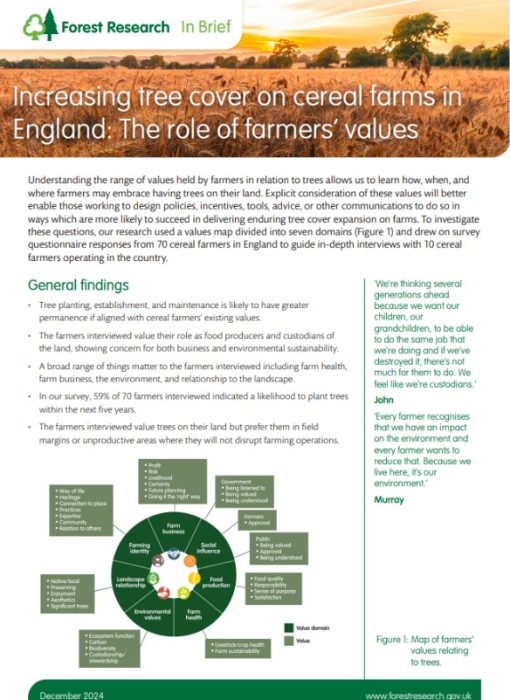

Overview Woodland creation and management deliver a wide range of environmental benefits. The extent of those benefits is determined by…

Lead Author: Joe Beesley