Considering there are currently some 27,000 km2 (2.7 million ha) of land in Great Britain under woodland management it is inevitable that a significant part will contain sites of archaeological importance. Any archaeological evidence is part of a dynamic environment and its management can be a complex issue. Often, the first difficulty for a woodland manager is to identify any relevant features. While many are mapped or recorded, locating them on the ground may be problematic. Every site or feature will need some degree of management to minimise the risks of any damage. Examples of some management issues are outlined below.

Considering there are currently some 27,000 km2 (2.7 million ha) of land in Great Britain under woodland management it is inevitable that a significant part will contain sites of archaeological importance. Any archaeological evidence is part of a dynamic environment and its management can be a complex issue. Often, the first difficulty for a woodland manager is to identify any relevant features. While many are mapped or recorded, locating them on the ground may be problematic. Every site or feature will need some degree of management to minimise the risks of any damage. Examples of some management issues are outlined below.

The retention of tree cover may also be desirable for its own historical value. For example where archaeological evidence is directly associated with past woodland management or sites occur in areas of ancient woodlands. With sensitive management, tree cover upon or surrounding suitable types of archaeological site could provide long term, low cost, physical protection. To maintain tree cover whilst minimising the risk of damage to any archaeological evidence, some form of active forest operation such as thinning or harvesting will be required during the tree’s lifetime.

On some sites, there will undoubtedly be a need for tree removal this can be a very successful operation. The most frequently quoted example of removal is where mature trees are at risk from windthrow. However, the effects of tree removal must also be considered, as it will cause change in the surrounding environment and may have unforeseen impacts upon the remaining archaeology. Potential problems can also arise from increased visitor pressure with examples of archaeological damage resulting from the use of bikes on earthworks. Additionally, where former woodland management has been withdrawn from large areas, scrub, gorse (Ulex europaeus) and bracken (Pteridium aquilinum) may invade creating a new set of conservation issues.

The types of archaeology found within forests or woodlands are very diverse and of varying degrees of importance. Similarly, the site conditions in which they are found and the local flora and fauna also differ greatly. With such variation, general recommendations on site management are difficult. For a site-specific, optimum management strategy to be determined, more information would ideally be available on the type of archaeological feature, its importance, its depth if buried, its composition and also on site details such as soil type, altitude, exposure, slope etc. and proposed crop details. Professional judgement on a site-by-site basis is always needed. Nevertheless, proper discussion of both the advantages and disadvantages of a woodland and other vegetation cover will promote a better, more informed management.

The types of archaeology found within forests or woodlands are very diverse and of varying degrees of importance. Similarly, the site conditions in which they are found and the local flora and fauna also differ greatly. With such variation, general recommendations on site management are difficult. For a site-specific, optimum management strategy to be determined, more information would ideally be available on the type of archaeological feature, its importance, its depth if buried, its composition and also on site details such as soil type, altitude, exposure, slope etc. and proposed crop details. Professional judgement on a site-by-site basis is always needed. Nevertheless, proper discussion of both the advantages and disadvantages of a woodland and other vegetation cover will promote a better, more informed management.

Within the Forestry Commission estate, important archaeological sites are incorporated into the Forest District Conservation Plan where appropriate management is prescribed. Each Scheduled Ancient Monument (SAM) has its own specific management plan, agreed with the appropriate national heritage body. Forest Enterprise has undertaken to periodically review the condition of SAMs on the estate, and their respective management plans. All known archaeological sites are incorporated into individual forest design plans and consideration of their role and setting in the surrounding landscape is encouraged.

There are too many archaeological sites in the UK to manage them all as open grassland. Tree cover on, or surrounding, suitable sites may offer a form of long term, low cost, physical protection. Forests have arguably prevented the destruction of some archaeological evidence compared with other agencies such as intensive agriculture or commercial development. Additionally, many archaeological features such as saw pits of charcoal platforms, are directly associated with the woodland’s history and its past management. Thus, tree removal may be inappropriate.

There are many potential ways in which tree cover can influence archaeological evidence, but the likelihood of any impacts are also dependent of a range of site-specific variables. With many of these issues, management options can be implemented to reduce any risks and develop a suitable mitigation strategy. This requires sensitive management with an informed understanding of the potential risks, the available options and their consequences. However, for the majority of these potential issues, there is a need for a greater understanding.

Some examples of potential issues where trees are retained include:

Archaeological literature reports well preserved remains under woodland but they usually refer to monument form, and impacts below ground have often not been investigated. Such investigations in woodlands are few, as physical surveying and excavation is more problematic. Two studies in Scotland have been commissioned to specifically assess the impacts of the cultivation used prior to afforestation and subsequent tree rooting. At both sites, the archaeological evidence occurred within the rooting zone, but the reports concluded that the majority of damage was caused by cultivation, and that root induced problems were local and did not prevent archaeological interpretation. However, the reports identified the need for further research on a wider range of soil types, tree species and archaeological evidence.

Where the decision has been made to remove trees from sensitive sites, they are usually felled, and the stumps left in situ, thus minimising below ground disturbance. The remaining stump and root system can still produce growth long after the stem has been removed. Many tree species (especially hardwoods) are renowned for their ability to produce new vegetative growth (coppice shoots), but this differs with tree age and species. As any regrowth will ensure the continued growth of the root system, fresh stumps may be given an application of herbicide. The practicality of this process may be limited, as herbicide is often only translocated a short distance into the stump and its application may be environmentally undesirable.

Where plenty of notice is possible prior to felling, a process known as “ring barking” may be employed. This prevents newly synthesised nutrients from being stored in the roots and those present become depleted. The tree can subsequently be felled with little chance of either coppice or sucker growth.

Once severed from the stem, roots will be subject to attack from soil micro-organisms, resulting in the eventual loss of root integrity. Once decayed, voids are left within the soil. Water can drain through these channels and the surrounding soil and will creep in from the sides. Any organic material derived from the root itself may be mixed with the soil by bioturbation. Such voids may cause problems where movement of soils, deposits and artefacts occur, thus confusing the stratigraphic interpretation and archaeological context.

The removal of trees from within an area of woodland can put adjacent trees at risk from windthrow. At particular risk are dense upland conifer plantations, often grown on poor or thin soils producing trees with potentially shallow root systems. If areas within such forests are opened up to expose archaeological sites, the trees on the newly created edges are at risk of windthrow due to poorly developed root system and a sudden increase in exposure. Such implications must be considered prior to opening an archaeological site within any woodland.

Following tree removal from an archaeological site, some form of management will be required to prevent invasion of unwanted weed species that would normally be suppressed under a closed tree canopy. Frequently, the preferred management option on archaeological sites is grazing. However, overgrazing can cause surface soil erosion, and stock control requires careful management. On many sites within woodland clearings, grazing is often undesirable due to risk of damage to adjacent trees or simply impractical for other reasons.

As well as possible detrimental effects from root growth of invasive vegetation, it can also mask archaeological features and put them at risk from accidental damage such as the movement of vehicles during site management. Colonizing species vary from one site to another depending upon factors such as geographic location, soil type, altitude, exposure and neighbouring species. Smaller woody shrubs also take advantage of open land, and gorse (Ulex europaeus), broom (Cytisus scoparius) or rhododendron (Rhododendron ponticum) may be a problem locally.

Non-woody species such as bracken (Pteridium aquilinum) can also be very invasive. With its main rhizome penetrating at least 0.4 m into the soil (fine roots deeper) and with a lateral growth rate of 1 to 2 m a year, the impact of bracken should not be underestimated. Bracken is also less palatable to sheep than many other plants and so grazing may not be a successful means of control. Where it has become established, current control methods require a very intensive cutting regime or extensive use of herbicide, a process that many landowners prefer to avoid. Additionally, mechanised weed control following tree clearance, such as mowing, may be hampered by the presence of tree stumps.

To maintain an archaeological site in open grassland, vegetation management will usually be required and possibly further measures to avoid erosion or to control burrowing animals. Nevertheless, the opening of areas through purposeful deforestation in the interests of both the archaeological evidence and their landscape setting has been successful in many places.

All important archaeological earthworks will need an active management to prevent the establishment/proliferation of unwanted vegetation types and reduce the risk of monument damage or enhance its setting. Vegetation monitoring (even in its simplest form) should be considered, as it provides a method of assessing the effectiveness of management plans. And, when combined with GIS, also allows longer-term changes in both the condition of the monument and its environment to be examined.

To develop suitable methods, vegetation monitoring is occurring on a sample of monuments in southern England at three levels of intensity:

Archaeological literature contains many references to animal-induced site damage. Examples include erosion caused by the overgrazing of sheep, cattle, burrowing damage by rabbits and badgers. Where trees are present in conjunction with livestock, they may be used for shade, shelter or as scratching posts and this has occurred on earthworks such as large burial mounds where a few trees grow on the summit. Here the trees will act as a focal point for any grazing animals that have access to them.

Many woodlands now contain open areas designed to increase their biodiversity and ecological value. Where a woodland is to have a glade created, and archaeological evidence exists, there may be a desire to combine the two by creating the glade around the feature. Where both occur together, fences may be needed to exclude larger animals from the feature. Glade creation will often attract an increased number of deer and many burrowing mammals prefer open ground with adjacent woodland shelter rather than dense canopy cover. Other site factors such as soil type, drainage and geographical location will also have an influence on the mammal species that will utilise the site. Depending on the type of archaeological feature, the active encouragement of mammal species may not be complementary to its conservation.

It is Forestry Commission policy to increase public access to its woodlands and recreation, tourism, health and well-being are considered of greater importance today than they have been in the past. Some Forest Districts are now utilising their cultural assets and creating heritage walks with information signs that incorporate features of interest. Such trails attract more visitors to the woodland and thus provide both health and educational benefits.

However, careful management is needed when promoting access to heritage sites and features. Careful consideration regarding heritage conservation is required to determine the likely visitor impacts.

Where visitor numbers are likely to be high, suitable paths may need to be created to either keep the public away from the most sensitive areas or to protect the monument beneath thus providing some form of erosion control. In extreme cases, vandalism may occur. For example, on Dartmoor there have been incidences where many smaller stones from monuments have been moved by the public.

The lighting of fires is also very common inside burial mounds and henge monuments, and in many cleared forest areas, fly-tipping is a possibility.

Within the Forestry Commission estate, each Scheduled Ancient Monument (SAM) has its own individual management plan (agreed with the relevant national heritage body) and these are subject to periodic review. However, many unscheduled sites are also of high local or national importance and need some degree of management to reduce any risk of damage.

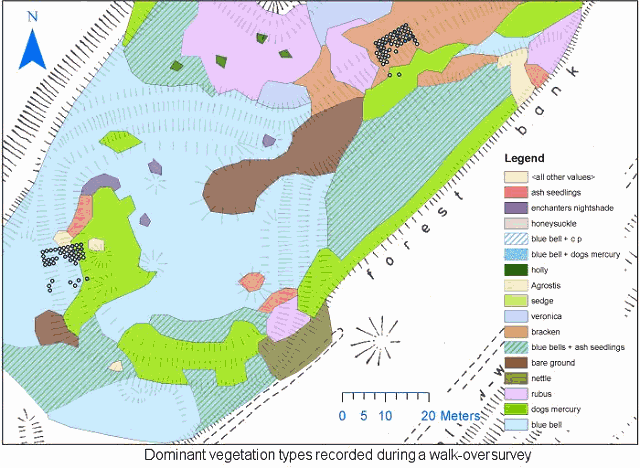

Dominant vegetation types recorded during a walk-over survey:

It is not possible to visit every archaeological feature on a regular basis to assess the effectiveness of management plans and some form of monitoring system is required to show any changes with time. For example, where trees are retained, any degradation in their health may indicate a need to fell them prior to any windthrow. Equally, the presence of a new animal burrow may require prompt action to prevent extensive damage to an earthwork.

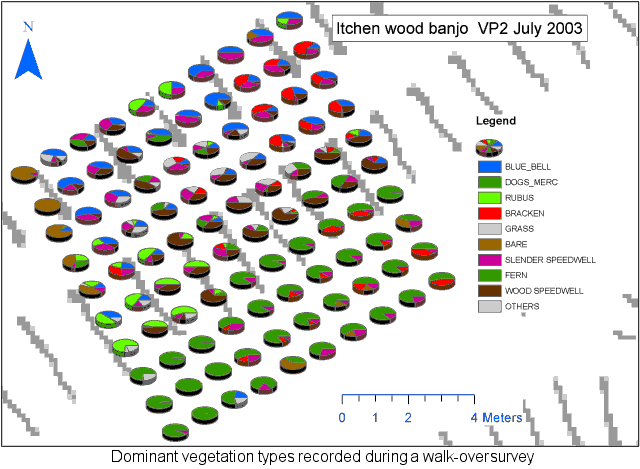

A detailed survey of one area showing the percentage ground cover:

Such a system is currently being devised within the Forestry Commission to highlight changes in the monument and its surrounding environment to identify immediate risks and inform the revision of management plans. This will be incorporated into the GIS used for most management and operation decisions.

Damage to archaeological evidence

Damage to archaeological evidenceWhen a tree is thrown and the root-plate heaved up, it will inevitably lift soil with it. This will elevate or expose any near-surface archaeological material, may cause physical damage and remove the evidence from its correct context. Many factors influence the susceptibility of trees to windthrow (such as location, soil type, species and woodland management) and considerable research has been undertaken to understand the relationships between them. Upland conifer plantations are often sited on thin or waterlogged soils producing trees with shallow root systems. If tree felling occurs around archaeological sites in these plantations, this can increase the exposure and risk of windthrow to the remaining trees. Thus, forest felling plans must take this risk into account.

Modern technology has allowed the evolution of windthrow prediction. Early methods for scoring windthrow susceptibility considered the region of the country (wind zone) in which the site occurs, the elevation, exposure, soil type and aspect. These were then related to the tree height and stocking density, factors which are especially important for upland forests at higher risk from windthrow. A more recent computer based model (ForestGALES) uses additional information on the crop and silvicultural regime.

In upland areas where the risks from windthrow are greatest, windthrow predictions should be made before deciding to open up an archaeological site, improve access or enhance the landscape setting. If a few trees exist on a burial mound and are at risk of windthrow, then pruning the tree and removing some of the above ground biomass may be an alternative to felling. This will reduce the risk of windthrow whilst maintaining the structural integrity of the slope. Such advantages are seen in coppice silviculture.

Coppice management

Coppice managementWell maintained coppice stools can, in principle, be worked indefinitely, although this is usually limited by nutrient availability and stool mortality. Oak coppice can be economically maintained for up to 130 years cut on a typical rotation of 6-30 years. An alternative method of management is coppice with standards. Here a single shoot from each stool is not coppiced on the normal rotation but left to develop into a timber quality stem. This method has historically been the standard practice and ancient coppice stools (several hundred years old) are common. Coppice systems (without standards) have the benefit of minimal soil damage during harvest, a reduced need for weed management, physical protection of the site, negligible risk of windthrow and where markets for the product exist, a cash return for the landowner. Nevertheless, concerns may still exist over potential damage to archaeological remains due to root penetration.

The long life of structural tree roots may provide a stabilising lattice to support the form of an earthwork such as a bank. Where appropriate and possible, coppice silviculture may offer long-term soil stability with reduced risk of windthrow compared with high forest management. Knowledge of the rooting habits, water requirements and the environmental chemistry under different tree species can also be used to reduce risks of some potential impacts.

Coppice root systems consist of finer, less extensive roots than standard trees that are subjected to some degree of checking following coppicing. With their long life potential, coppice stools may offer an alternative to grass where grazing or intensive management is not an option, or to standard tree cover where associated operations and larger, deeper rooting are less desirable.

The primary functions of roots is to provide nutrients, water and support for the above ground component of the plant. As a direct result of this function, the above-ground tree biomass is directly related to the root biomass and vice versa. The “root:shoot ratio” is a relatively constant value but will vary slightly with species, site conditions and silviculture. It is believed that the process of pruning reduces the surface area of the tree available for photosynthesis that in turn lowers the total amount of carbohydrates available to feed the root system. Once the root reserves are used, the excess root will die until the ratio is re-established.

Further information on coppice roots can be found on the Short Rotation Coppice page.