Summary

Summary

Landscape ecology is an exciting and rapidly evolving discipline that is highly relevant to the ecology and management of British forests.

- The Forestry Commission recognises the need to consider biodiversity in modern multi-use forestry.

- Biodiversity is threatened by the fragmentation of woodland and other semi-natural habitats. Fragmentation affects both the physical structure of the landscape and its ecological function for the species within it.

- Biodiversity protection is most effective when actions at the landscape scale are combined with site-based measures.

- Landscape ecology research can be applied to modern forestry and landscape management through the effective targeting and evaluation of landscape change.

Research objectives

- DEVELOP our approach to landscape scale biodiversity action using the most advanced scientific principles.

- CONSTRUCT a suite of tools for landscape scale biodiversity analysis.

- APPLY, evaluate and refine the tools using real case study landscapes, covering a range of scales and issues. Each case study has a direct application for (and is often commissioned by) forest managers.

- EXPAND our knowledge of species-landscape interactions.

- DELIVER a suite of user-friendly tools to help Forestry Commission and other land management agencies deal with strategic and operational issues.

Funders and partners

![]()

This work has been developed through core funding from the Forestry Commission Habitat management, protected species, biodiversity, genetic conservation and forest reproductive materials programme, and contract research funded by:

- Forestry Commission England

- Forestry Commission Scotland

- Forestry Commission Wales

- Scottish Natural Heritage

- Countryside Council for Wales

- European Union

- Scottish Government Rural Development Department (formerly Scottish Executive Environment and Rural Affairs Department – SEERAD)

- Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra)

Forestry Commission policy

The need to conserve woodland biodiversity and combat habitat fragmentation is a key element of the biodiversity and forestry strategies for the UK. This originates from the Earth Summit in Rio in 1992, from which followed the Convention on Biological Diversity and the Resolution for the Conservation of Biodiversity in European Forests signed in Helsinki in 1993.

In addition the UK Government developed the Biodiversity: the UK Action Plan and in 1995 published the Species Action Plans and Habitat Action Plans, which conclude that:

“One of the principal threats identified in many of the species conservation action plans is that posed by habitat fragmentation.”

The Forestry Commission’s Forestry Strategy Documents for the devolved countries of England, Scotland and Wales outline the threat of biodiversity loss from habitat fragmentation. In particular, the strategies for Scotland and Wales stress the need for woodland expansion in the form of habitat networks, to protect woodland biodiversity.

Publications and articles

- Biodiversity in fragmented landscapes (PDF-1870 KB)

Forestry Commission Research Note 10 - Evaluating biodiversity in fragmented landscapes: Principles (PDF-488 KB)

Forestry Commission Information Note 73 - Evaluating biodiversity in fragmented landscapes: Applications of landscape ecology tools (PDF-1479 KB)

Forestry Commission Information Note 85 - Evaluating biodiversity in fragmented landscapes: The use of focal species (PDF-3551 KB)

Forestry Commission Information Note 89 - Landscape ecology: emerging approaches for planning and management of forests and woodlands within Britain (PDF-582 KB)

Article from Forest Research Annual Report 2004-5 - British Forest Landscapes – The Legacy of Woodland Fragmentation (PDF-485 KB)

Kevin Watt’s article that won the Royal Forestry Society’s (RFS) 2006 James Cup, which is awarded each year to the author of the best article published in its Quarterly Journal of Forestry

Future developments

- Developing realtime links between our suite of tools and the Habitats and Rare Priority and Protected Species (HaRPPS) decision support system.

- The importance of landscape ecology to urban green networks.

- Liasing with geneticists to discover how organisms move through the landscape.

Related Forest Research programmes

- Habitat networks

- Species action plan research

- Impacts of large herbivores on woodlands

- Ecological Site Classification

- Biodiversity Indicators and Knowledge Management

The rural and urban landscape ecology (ruLE) group is a wider group within Forest Research including researchers who cover a range of landscape scale issues.

Status

The programme began in 1999 and is ongoing.

Contact

Tools and Methods in Landscape Ecology

Background

Background

The National Assembly have strategic objectives to target woodland expansion in order to connect existing woods, increase the core area of native woodland habitats, and foster linkage to other semi-natural communities, as outlined in the Forestry Strategy Document for Wales. The Countryside Council for Wales (CCW) and the Forestry Commission Wales (FCW) are collaborating to develop and implement a woodland habitat network in Wales.

The overall research aim is to design and build a spatial framework and supporting analysis to advise the CCW and FCW, and partners, on the potential for the development woodland habitat networks in Wales. The research is intended to inform a strategic plan for the maintenance, improvement and restoration of woodland and associated habitats with the aim of combating the effects of habitat fragmentation.

The work is due for completion in late 2006/early 2007.

- Land cover thresholds have played an influential role in explaining and developing habitat networks within the UK. We reviewed the principles of land cover thresholds, particularly the 30% cover rule, and explored them to assess their usefulness in the development of habitat networks.

- Woodland habitat networks

A focal species-based approach to develop and define woodland habitat networks, using an accumulated cost-distance buffer model within the BEETLE (Biological and Environmental Evaluation Tools for Landscape Ecology) set of tools. - Strategic aspects

- Understanding open non-woodland habitats

- Assessment of marginal network areas

- Large-scale linkages and climate change

- Strategic validation of networks and linkages.

- Local level

- Case study sites

- Refinement of networks

- Local validation of networks

- Implementation of networks.

Report

Towards a woodland habitat network for Wales (PDF-3519 KB)

Report No 686 – A collaborative project between CCW and Forestry Commission, Wales

Useful sites

Landscape ecology – Spatial pattern in UK forest landscapes

Neutral landscape models (NLMs) with 30% woodland cover

Random clustered

Low clustered

High clustered

Land cover thresholds have played an influential role in describing the pattern of landscapes, particularly the 30% cover rule.

Landscape metrics

A number of landscape metrics (number of patches, total edge, largest patch, total core area) which exhibit land cover thresholds were applied to a range of neutral landscape models, which varied in their degree of spatial clustering and ‘actual’ Welsh woodland landscapes.

Applying simple thresholds

The concept of simple landscape thresholds, derived from random landscapes, is very appealing to aid the development of such plans and strategies. However, our results indicate there are considerable differences between random landscape elements and the Welsh landscapes, highlighting the likely problems of practically applying simple thresholds derived from the former.

Woodland clustering

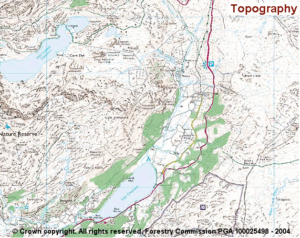

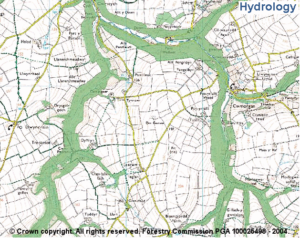

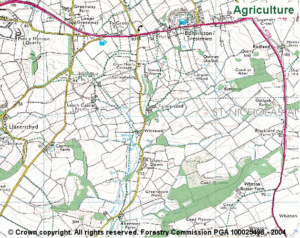

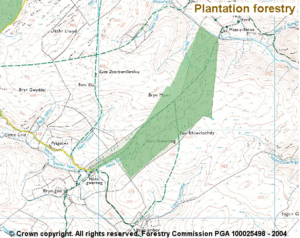

The results confirm that the distribution of Welsh woodland is spatially clustered and not random, and associated with a combination of factors including topography, hydrology and land use:

Welsh woodland has greater similarity with the highly clustered landscape models. Interestingly, such models do not exhibit the same clear thresholds as the random landscapes.

Ordnance Survey maps: © Crown copyright. All rights reserved. Forestry Commission PGA 100025498 – 2004.

Landscape ecology – Isle of Wight

To continue taking the network approach forward these issues need to be addressed at a more local scale through the use of smaller scale case study areas. Changing the scale of analysis from the strategic to the local scale may help to refine, validate and implement habitat networks. Information gleaned from these case studies will provide insights and be used to inform strategic level work.

Selected case study sites

Three pilot case studies will be used to explore issues at a local scale. The proposed case studies represent important habitat networks and represent the diversity in Welsh landscapes and a variety of different landscape issues.

| Area | Features of interest |

|---|---|

| ‘Meirionnydd Oakwoods’ SAC (confirmed) |

|

| Gower Peninsula (provisional) |

|

| Montgomeryshire ancient woodland (provisional) |

|

Refinement of networks

The use of local information will allow for the refinement of the previously identified Core and Focal Networks in each of the study areas. To do this, modelling work will be undertaken which incorporates more detailed habitat information. Where possible this will include further habitat information within the landscape matrix such as hedgerows, scattered trees, wood pasture and different types of scrub. The habitat networks may also be refined by acquiring data on their habitat quality which will give an indication of the effective area of a woodland polygon and allow for an extension of the previous network modelling.

Local validation of networks

In addition to the strategic validation with species and site data, it may be possible to use the refined networks and additional species information/distribution data to produce new habitat/focal species models, for locally important species. From this it will be possible to infer the effectiveness of the defined networks. This work will be limited by the amount of autecological data available for selected species.

Implementation of networks

The implementation of a habitat network strategy must take into account the effects of the strategy on wider landscape sustainability issues. The local case study scale is the appropriate stage to bring in the objectives and interests of the wider environmental and socio-economic stakeholders.

What’s of interest

SAC: Special Areas of Conservation

Landscape ecology – Forest Habitat Network for Wales

Understanding open non-woodland habitats

Expanding woodland habitat networks may potentially disrupt or impede the functioning of open (non-woodland habitat) networks. Therefore, there is a need to understand the distribution of open habitat networks in Wales and to identify any potential conflict areas. The results of this analysis will give a good strategic knowledge of the open non-woodland habitat networks in Wales. Analysis will be based around the overlap between these networks and woodland networks, which will start to show potential areas of conflict. The potential for negative effects of woodland habitat networks would be resolved at a more local scale.

Assessment of marginal network areas

A further assessment of areas that have considerable woodland cover but fragmented into many networks will be undertaken. These areas may have a great deal of potential for biodiversity conservation but are not highlighted in the previous work.

Large-scale linkages and climate change

The global mean temperature increase of 0.6 °C has changed rainfall patterns, caused a rise of sea level and increased the frequency of extreme events. It is predicted that global temperatures will rise further by 2 to 4.5 °C by 2100. In Wales there are predictions of increased warming in the summer months – more intense in the south and east compared to the north and west. Wales could see significant increases in winter rainfall, a 50% reduction in summer rainfall, with snowfall becoming a rarity. These climatic changes will have a significant impact on the biodiversity of Wales, and on the wider landscape, beyond semi-natural habitats, due to adjustments in the intensively managed land within agricultural systems.

The project proposes the mitigation of climate change through the development of improved functional connectivity between key networks across the main biogeographic axes of Wales, through the use of large-scale linkages or corridors. The linkages will be long term and to an extent aspirational, but will offer the opportunity to develop a management framework that explicitly addresses the issue of climate change beyond the scale of Core and Focal Networks.

Strategic validation of networks and linkages

Species records held by the National Biodiversity Network (NBN) and the Countryside Council for Wales (CCW), and information on protected sites held by CCW will be used to further validate the existing networks and the proposed large-scale linkages. The selected species will represent important species for woodland and open habitats in Wales.

Useful sites

Landscape ecology – Forest Habitat Network for Clocaenog Forest

Modern forest design planning has to take account of multiple environmental, economic and social uses.

Modern forest design planning has to take account of multiple environmental, economic and social uses.

To further understand the impact of forest design planning on biodiversity, there is a need to examine changes to the spatial and temporal distribution of particularly important habitats, such as open and mature forest, through the forest planning process. Important elements of UK biodiversity are often associated with these open (e.g. black grouse, small pearl-bordered fritillary) and mature conifer habitats (e.g. red squirrel).

Within Clocaenog Forest, a 5500 hectare conifer plantation in north Wales, we are starting to examine the planned spatial and temporal changes in open and mature conifer habitats and their potential impact on key species. Many forests are now planning change to meet current and future objectives e.g. continuous cover silviculture. A high level of detail in terms of land cover; coupled with new GIS techniques for modelling future forests, is allowing us to explore these patterns at an increasingly fine spatial (Figure 1) and temporal (Figure 2) resolutions.

The impacts of changes on the small pearl bordered fritillary (Boloria selene, a butterfly listed as a Species of Conservation Concern) are currently being surveyed, so we can construct and test spatially explicit population models.

Figure 1.

Future forests software represents the age structure of subcompartments (individual planting units) of Clocaenog Forest (5500ha) under various management scenarios. In this scenario, mature conifer and open habitats are maximised.

Figure 2.

Knowing the area of each habitat type each year over the next 30 years allow us to construct population models for the rare species there. Under current scenarios, open areas will remain relatively constant, whereas mature habitat will increase by around 50 percent by 2030.

Related pages

Useful sites

Landscape ecology: Developing the evidence in landscape ecology

Much of the work of Landscape Ecology is based on the principle of functional connectivity (that species movement is affected by patch size, isolation and the landscape features between patches). Our current research into how the landscape features between patches affect species movement forms three strands:

- Monitoring species movement

- Landscape genetics

- Systematic review and meta-analysis

This research is used to support forest planning and validate our landscape modelling. Here we present an example from each strand.

Monitoring species movement: Small pearl-bordered fritillary

For eight years 2001 – 2008, the occurrence and numbers of the small pearl-bordered fritillary Boloria selene has been monitored in Clocaenog Forest in north Wales. In collaboration with Butterfly Conservation, we have been able to show that the species acts as a meta-population, where patches can become unpopulated and then be recolonised over time. In 2002, mark-release-recapture experiments were carried out. Of the 321 butterflies marked, only seven were recaptured in a different patch from their mark patch. These travelled up to 3 km across the forest, it is believed they use open and riparian areas and avoid dense mature conifer stands, but we do not know the exact route taken by each butterfly.

We are comparing these few movements, plus the rates at which empty patches get recolonised, with various ‘scores’ for the permeability of the different forest stands, open spaces and rides along possible movement routes.

Landscape genetics: Wood crickets

The wood cricket Nemobius sylvestris was the subject of a PhD by Niels Brouwers, in collaboration with Bournemouth University. Niels’ work suggested that wood crickets were a woodland edge species and unlikely to cross fields, water or roads. In 2007, in collaboration with the genetic conservation group we caught over 1000 wood crickets in different woodlands on the Isle of Wight, along with samples from three populations on the mainland. We have analysed 15 microsatellite markers to see how related the populations were within and between woodlands. We are now exploring the relationship between genetic similarity and the distance between populations, taking into account alternative permeability values for the intervening landscape.

Systematic review and meta-analysis

Systematic review is a tool used to collate, summarise, appraise and communicate the results and implications of a large quantity of research and information. It can support decision-making by providing an independent and objective assessment of evidence. In collaboration with the Centre for Evidence Based Conservation at Bangor University, we looked at the evidence that matrix features affect species movement.

We included 315 articles and reports in our review. We used a statistical technique called meta-analysis to combine the results from different studies and look at the variation in the outcomes of the studies.

The pattern that emerged from all the (frequently conflicting) evidence is that matrix features that are more similar to the breeding habitat of a species will tend to increase species movement. However, there is lots of variability and this seems to be down to species behaviour.

Relatively mobile groups like butterflies, birds and large herbivores seem to benefit from increased connectivity. For these species, spatial targeting of measures to create corridors and a matrix with structural similarity to the “home” habitat should enhance population persistence and may promote longer distance movement. However, there were many species for which no information was available.

- Systematic review report

- Which landscape features affect species movement? A systematic review in the context of climate change (PDF-1180 KB)

Final report to Defra

What’s of interest

Metapopulation

A group of subpopulations in which individual subpopulations occasionally go extinct and are later re-colonised from other ones.

Microsatellite markers

Very variable bits of DNA that are thought to mutate at a fixed rate without affecting individual ‘fitness’ or reproduction. They can be used to look at how related a group of individuals is.

The ‘basics’ of landscape ecology

Landscape ecology is the study of the interactions between the temporal and spatial aspects of a landscape and the organisms within it.

Landscape ecology is the study of the interactions between the temporal and spatial aspects of a landscape and the organisms within it.

What do we mean by ‘landscape’?

It is worth observing that though fashionable, the use of the term ‘landscape’ is often applied rather loosely, and can include:

- A focus of attention, and a perceived quality often based on aesthetics e.g. ‘landscape planning’, landscape character areas, landscape view.

- A spatial scale and extent expressed in geographic terms e.g. ‘landscape scale’, several square kilometres.

- An arena within which to target action, e.g. projects aimed at forest landscape restoration.

- An entity with structural elements of patch, mosaic and corridor, reflecting a mix of ecosystems and habitats.

Many ecologists consider ‘landscape’ to be the latter point, any unit of the earth that contains heterogeneity: in vegetation structure, habitat type, soil type or any other attribute which could mean that organisms might react differently to different parts.

Lowland agricultural landscapes form typical ‘landscape mosaics’, with intermingled patches of woodland, arable fields and pasture, divided by hedgerows and roads

Much of landscape ecology has developed around the paradigm of a landscape mosaic consisting of patches (of e.g. habitat) arranged in a matrix (the predominant habitat or land cover), with elements that can be described as corridors, barriers, and edges. For more on the way landscapes can be divided into structural elements, read Landscape Ecology by RTT Forman & M Godron (1986, Wiley).

A question of scale

Landscape ecology research in British forestry has historically focussed on the area within the forest boundary but is now more likely be considered within catchments or other topographic or administrative units. Our definition of landscape scale is determined by the particular research issue being addressed. The appropriate scale may therefore vary from the forest (several square kilometres), through to the catchment or region (tens to hundreds of square kilometres) or to whole country (hundreds to thousands of square kilometres).

How do organisms interact with the landscape?

This question is the focus of a vast amount of research effort globally, but the following are some notable examples to give the general idea:

- Patches: species may prefer a certain kind of habitat, for example mature woodland, or ponds. Individuals of the species of concern may not be able to breed or feed outside this type of habitat. The habitat thus defines the patch.

- Matrix: If one land use dominates the landscape, that land use forms the matrix, e.g. arable land in eastern England. If the dominant land use is uniformly inhospitable, organisms become isolated in patches of suitable habitat. For example, some characteristic plants of ancient woodland cannot survive in arable fields, and do not have seeds equipped with a mechanism to disperse between isolated woodland fragments.

- Corridors: There has been a lot of research and debate about the role of hedgerows as corridors for small woodland mammals and birds. Such species may be able to move between woodland habitat patches along hedgerows, whereas they might not feel safe enough to cross an arable field.

- Barriers: Roads, pipelines or fences might form barriers to movement of shy or less agile animals.

- Mosaic: Lesser horseshoe bats are an example of an animal that needs to live in a landscape mosaic. They sleep in old trees in mature woodland, then fly along hedgerows to open, wet places where they hunt for flies.

Scientific Principles of Landscape Ecology at Forest Research

- Fragmentation

- Landscape structure and function

- Connectivity

- Individual focal species

- Generic focal species

Fragmentation

Broadleaf woodland (very dark green) within a highly fragmented agricultural landscape

The fragmentation of woodland habitat into smaller isolated patches poses one of the key threats to forest biodiversity. Fragmentation:

- Reduces the total amount of habitat area

- Increases edge effects around habitat patches reducing core area

- Increases patch isolation.

According to a number of scientific theories, such as island biogeography and metapopulation dynamics, the reduction in area may lead to increased local extinctions, while increased isolation may cause a reduction in the exchange of individuals between isolated patches, threatening their long-term viability.

Landscape structure and function

Land management activities which change landscapes have an impact on both the structure and function of the landscape. It is predicted that such changes, which include fragmentation, will influence the ability of biodiversity to survive within, and move through, the landscape. In terms of evaluating biodiversity, it is necessary to assess the impact of changes upon both structure and function.

The structural element refers to the spatial arrangement and organisation of distinct landscape elements. Analysis is often focused towards the physical composition and configuration of particular habitat patches within a landscape.

Landscape function is concerned with the interactions between these structural elements, through ecological processes and the flow of energy. In terms of biodiversity, landscape function is often related to the movement and viability of particular species within these structures.

Connectivity

Connectivity is a landscape characteristic that encompasses habitat amount and isolation. It is important to assess both the structural connectedness and the functional connectivity within a landscape. The latter occurs when individuals are able to move between habitat patches.

Functional connectivity depends upon both the arrangement of suitable sized patches (Figure 1) and the matrix (non-habitat land use) in between them – more intensive land uses being resistant to movement for some species (Figure 2).

Species – landscape interactions

Assessing landscape function requires some information about how biodiversity interacts with landscape structure. We can analyse landscapes for individual species of particular interest or set parameters which protect whole groups.

Individual focal species

We may analyse connectivity for a range of individual species for different reasons, e.g.

- target species of intensive conservation effort such as the red squirrel

- keystone species believed to support a large part of ecosystem function

- umbrella species whose protection is believed to be adequate to protect a range of other species

- flagship species which people are motivated to support.

The term ‘focal species’ is somewhat contentious. Lambeck’s (1997) definition uses ‘focal species’ to set parameters for reserves according to the most rigorous requirements of the suite of species present. For example, whilst the area requirement could be set by one species, the connectivity requirement could be set by another. For our work ‘focal species’ simply means the species we are concentrating upon in that particular analysis.

The ecological information needed to analyse connectivity and fragmentation in a landscape is quite complex, especially the variation in the resistance, or permeability, of different landscape elements in the matrix. Focussing on an individual species may have negative impacts for other important species with different needs.

Generic Focal Species

These are an alternative to using individual target species for landscape analysis and evaluation.

A Generic Focal Species is a combination of ecological requirements that the modeller, to the best of their knowledge, thinks will cover the requirements of all the species they wish to account for in their landscape plan or evaluation. This is like an extension of the umbrella species concept, but without using a particular real species. The use of generic focal species defined by fragmentation sensitivity is currently an integral part of our Habitat Network model. The approach is not limited to Forest Research, as eco-profiles, which are based on a similar set of characteristics, are used by ALTERRA, a Dutch agency.

Evaluating biodiversity in fragmented landscapes: principles (PDF-488 KB)

Forestry Commission Information Note 73

What’s of interest

A metapopulation is a set of sub-populations which are dynamically connected by immigration and emigration.

Applications of Landscape Ecology in Forest Research

Targeting biodiversity action and evaluating landscape

There is a role for landscape ecology in both the targeting of actions to promote biodiversity, and also the evaluation of current and future solutions to support biodiversity in multi-use forest planning:

- The targeting element ensures the appropriate action is applied in the most effective areas, and to influence the development of multi-use landscape plans.

- The evaluation of planned landscape change, which will ultimately be a balance or compromise between the various environmental, economic and social objectives, ensures biodiversity is fully accounted for.

Prioritisation of management options

The order of strategic priorities for the improvement of wooded landscapes:

| Priority | Action | Area of application | Example specific to woodland |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Protect and manage the existing resource | High quality habitat | Ancient semi natural woodland; Special Areas of Conservation |

| 2 | Restore or improve degraded habitat | Target in areas with good restoration/improvement potential | Plantations on Ancient Woodland Sites (PAWS); sites invaded by Rhododendron ponticum |

| 3 | Improve the matrix | Areas of intensive land use | Increase in hedgerows in agricultural landscapes; reduction in pesticide/herbicide use; reduction in grazing densities. |

| 4 | Create new habitat | Target to improve size or connectivity of existing habitat. | Planting broadleaved trees suited to the site. |

Applied studies

Within the Landscape Ecology programme we apply, evaluate and refine our approach using real landscapes, covering a range of scales and issues. Each case study has a direct application for (and is often commissioned by) forest managers working in the real world.

Links to applied studies:

- Spatial pattern in UK forest landscapes

- Isle of Wight – evaluating untargeted and JIGSAW planting schemes (landscape structure)

- Habitat networks – functional connectivity analyses divided by region

- Wales – a range of approaches on a national scale including structural metrics, national and local aspects

- Clocaenog Forest – evaluating target species habitat use and functional networks in a plantation forest

- Lichen population dynamics.